Crafting a constitution is more than putting down rules on paper. It’s not a matter of boosting one man; it’s about establishing the architecture for an entire system of government that will serve all people for generations. Whether you are founding a country, establishing a campus group or organizing a neighborhood association, the presence or absence of good rules can determine whether your new society thrives or descends into mayhem; it can also mean the difference between freedom and despotism.

The truth is, there have been plenty of great-sounding constitutions that didn’t age well. Some had an inflexible ideology that left them unable to accommodate changed circumstances. The rest were so broad as to be meaningless. The hard part then isn’t just to write a constitution — the real challenge is to write one that actually functions in the world.

In this guide, we’ll take you through everything you need to know about building a constitution that grows old gracefully. You’ll see what works and what doesn’t from constitutions around the globe, learn what makes a constitution powerful, and walk away with practical steps to writing one that’s truly your own.

Why Most Constitutions Fail (And How Yours Can Succeed)

Before we address how to write a good constitution, let’s examine why so many fail. Know these pitfalls and avoid them.

The Problem With Perfection

Some designers of constitutions make a valiant effort to anticipate everything that could possibly happen. They produce behemothic documents with hundreds of articles, dealing with every last detail. The problem? Life is unpredictable. When your constitution is so specific, it’s out of date the moment you write it. The Soviet Union’s constitution, for example, guaranteed all sorts of rights, but was so out of touch with reality that it became a joke.

The Reverse Issue: Too Much Vagueness

Conversely, some constitutions are so vague that they do not actually say anything helpful. Rules that are too broad allow people in power to interpret them however they like. This muddies the waters, and gives political leaders too much power to abuse through their army even if they are technically abiding by the constitution.

Ignoring Your Country’s Reality

Many of the new nations have used constitutions borrowed from other successful states without reflection on their own condition. What works in America may not work in Kenya. Some things that work in Japan might fall flat in Brazil. Your constitution should be tailored to your culture, your history and that of today.

No Real Enforcement

A toothless constitution is a lovely piece of writing. If no one can enforce compliance with their rules or visit punishment on their transgressors, it will be ignored by leaders whenever it is convenient to do so. You need something built in to make sure the constitution is really relevant.

Essential Building Blocks for Every Working Constitution

So let’s move into the key components. These are the elements that every good constitution must contain, no matter who writes it or when.

A Clear Statement of Purpose

There should be a preamble at the beginning of your constitution that explains why you have this document. That’s not all decorative — it helps future generations comprehend what you were trying to accomplish. The “We the People” of the U.S. Constitution isn’t famous just because it sounds good. It unequivocally declares that the government derives its power from citizens, not kings or gods.

The preamble should answer the following questions:

- Who is creating this constitution?

- What are you trying to build?

- What values guide this document?

- What is the problem you are trying to solve?

How to Write a Constitution That Actually Works

Protected Rights That Will Not Be Taken Away

Every individual has certain rights that the government cannot trample over come what may. Human rights constitute the line that power cannot cross.

| Category | Examples | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Personal Freedom | Speech, religion, assembly | Lets people express themselves without fear |

| Legal Protection | Fair trial, no torture, presumption of innocence | Protects against abuse by the legal system |

| Political Rights | Voting, running for office, peaceful protest | Keeps government in check |

| Economic Rights | Property ownership, contract freedom | Allows people to build stable lives |

| Social Rights | Education, basic healthcare | Creates opportunity for all |

The trick is for these rights to be specific enough to amount to something, but flexible enough that they might also apply to futures you can’t now imagine.

Power Balance Through Division of Power

Power corrupts. This isn’t cynical—it’s just reality. Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power over one place only means greater abuse. Your constitution has to divide power among competing groups that will be able to restrain one another.

The least complex model involves three branches:

- Legislative branch makes the laws

- Executive branch enforces the laws

- Judicial branch resolves the disputes and interprets laws

But separation of powers extends further even than those three branches. You may also split power among:

- National and local governments

- Different chambers in the legislature

- The military and civilian leadership

- Public institutions and private organizations

A Practical Way to Change

So they’re the perfect storm in part because their constitutions are not very stable — for at least a century now countries have been altering them all over the place. Here’s a difficult balance to strike: Your constitution has to be relatively stable, that is, you don’t want it to constantly change, but also flexible enough to serve when it does need to change. If charter amendments are too easily made, then the constitution becomes redundant. If they’re too hard, the constitution becomes outdated.

Nearly all functioning constitutions stipulate a robust popular consensus to change them — say, two-thirds of the legislature or approval by a majority of states or provinces, or some kind of public vote. Some have needed to be approved in multiple steps, such as voting in favor of the measure during two successive legislative sessions.

The U.S. Constitution has been amended just 27 times in more than 230 years. Calculate amendments, however, and you need two-thirds of Congress to approve them and three-quarters of the states. Meanwhile, some countries revise their constitutions every few years because the bar is too low.

How to Write Your Own Constitution From Scratch

Ready to actually write? Here’s the process that works.

Step 1: Research and Learn

Don’t begin with a blank page. Read the constitutions of various countries. Review what worked and what didn’t. Give special attention to countries that have similar situations to you — proportionate size and culture, similar challenges.

Create a comparison chart:

| Country | Positive Example | Faulty Example | Lesson For Us |

|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. | Application 1: Strong court system | Weak local governments | Do not corrupt the judiciary |

| Example 2: Good amendment process | Too much executive power | Limit presidential authority | |

| Example 3: Clear rights protection | Weak right to vote; Complicated voting rules | Simplify procedures; Extension of term in office |

Step 2: Hear Out Real People

The kind of constitution you have impacts every person, so everyone should get a voice. Hold public meetings. Create surveys. Have real conversations with people from different backgrounds, areas, ages and economic levels.

Ask questions like:

- What rights are most important to you?

- What is wrong with our system now?

- What are you afraid will happen?

- What can be learned from examples of other places to emulate or avoid?

The example of writing South Africa’s constitution post-apartheid is a good one. They conducted public meetings nationwide and received millions of submissions by ordinary citizens. Such input lent the final product legitimacy and relevance.

Step 3: Assemble a Culturally Diverse Writing Committee

You need diversity at the table. Your constitutional committee should include:

- Legal experts who grasp how laws function

- Historians who are familiar with your country’s past

- Diverse group of community leaders

- Young people that will live the longest under such a constitution

- Pragmatic career politicians, who already know how government works

- Critics who will nitpick things that might otherwise go unnoted

Step 4: Outline Before You Start Writing

Discuss the overall structure beforehand, before writing text. Outline all of the major sections and what they cover.

One common structure would look like this:

- Preamble — Why this constitution exists

- Fundamental Principles — Core values

- Rights and Freedoms — What the government may not do

- Type of Government — How the power is distributed

- Powers and Duties — What the Branches Do

- Local Government — How places work

- Amendment Process — Change of the constitution

- Transitional Provisions — How to transfer from the old way

Step 5: Make It Readable

This is crucial. Your constitution is not some law school textbook. It needs to be comprehensible for normal people.

Poor sentence: “The legislature shall have power to pass laws on subjects of general welfare, subject to sections enumerated in this constitution.”

Good example: “The legislature may pass laws regarding the public welfare within such limits and subject to such restrictions as are imposed by this constitution.”

Avoid:

- Legal jargon that confuses people

- Sentences longer than two lines

- Hidden-agent passive voice

- Wishy-washy words that could be anything

Step 6: Add Examples and Explanations

Some constitutions are supplemented by short illustrations or notes explaining what various sections of the document mean. While the core text should be uncluttered, details can do heavy lifting to help people decipher complex provisions.

Step 7: Play With It in Different Situations

Before you finalize, go through several “what if” scenarios:

- What happens if the president won’t leave office?

- Why wouldn’t the courts and Legislature see this differently?

- What if an area wants to secede?

- What if there is a war or emergency?

- What if the military seizes power?

Your constitution should be an answer to these crises.

Step 8: Authorize It in the Right Way

The constitution needs legitimacy. This usually means approval through:

- Vote of convention for or against confirmation

- Ratification by current legislature (with high threshold)

- A national referendum in which the citizens vote directly

- Or some combination of these

The method is important because it will determine if people are willing to accept a constitution as legitimate.

Particularities Depending on the Type of Constitution

All constitutions aren’t created equal. Here’s how to adjust for different contexts.

For New Countries

If you are writing a constitution for a newly independent country, emphasize:

- Building institutions from scratch

- Addressing colonial legacies

- Bringing together different groups with varying interests

- Preventing the concentration of power

- Building a future that works for all of us economically

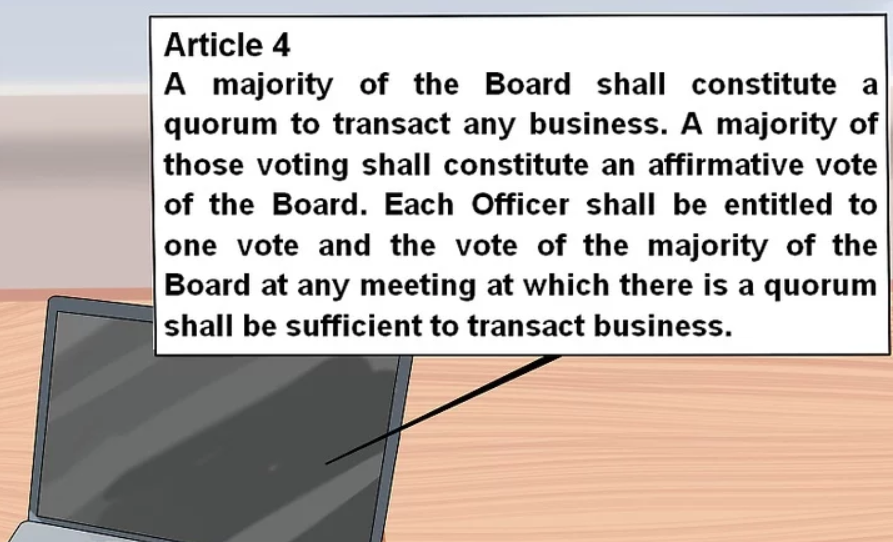

For Organizations and Clubs

Student clubs or community groups should also have a constitution on their side. Keep them:

- Short (2-5 pages maximum)

- Structure followed and carried out meticulous procedures

- Easy to amend as needs change

- Clear about member rights and responsibilities

For Reforming Existing Systems

When replacing an old constitution:

- Recognize what the old system got right

- Learn from specific failures

- Create a clear transition plan

- Prevent a reversion to old issues

Making Sure Your Constitution Gets Followed

Drafting the constitution is half the job. You have to have means of implementing it. See IDEA’s resources on constitution-building processes for international examples and best practices.

Independent Courts With Real Power

You need a healthy court system to be able to say “no” when the government is doing something that is unconstitutional. This means:

- Judges are (generally) much less palatable figures to the people whose following they would seek

- Transparent process for testing constitutionality

- Judicial decisions which are in force and effect

- Protection of the judiciary against intimidation and bribery

Regular Review and Assessment

Schedule mandatory reviews every 10 to 20 years. These aren’t occasions to throw the thing out and start anew, but chances to see whether the constitution is functioning as intended and make minor course corrections.

Education and Public Awareness

You can’t support a constitution you don’t value. Your system needs:

- Constitutional education in schools

- Public access to easy-to-read versions

- Civic groups that monitor compliance

- Media that cover the constitution

Consequences for Violations

The very constitution should detail what will occur when public authorities themselves defy the most fundamental law:

- Removal from office

- Criminal penalties for serious violations

- Nullification of unconstitutional laws

- Civil lawsuits for rights violations

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Let’s recap the biggest errors:

- Copying Without Reflection: What works in Germany isn’t guaranteed to work in Guatemala. Adapt, don’t copy.

- Too Long: If your constitution is 50,000 words long, no one will read it. Keep it focused on fundamentals.

- Excluding Enforcement: Rules without the stick of enforcement are recommendations, not rules.

- Disregarding Minority Rights: The majority cannot be allowed to tyrannize a minority by way of democratic voting.

- Ignoring Funding: Constitutional rights count for nothing if there’s no money to pay for them. Think about how things will be paid for.

- No Disaster Provisions: Crises are going to occur. Your constitution will need to set out what power the government holds in emergencies — and what limits remain.

- The Impossibility of Amendment: A constitution you can never change if needed will be ignored or overthrown.

What Success Looks Like

How can you tell whether your constitution functions? Look for these signs:

People Actually Mention It

Politicians, judges and the man on the street cite it—it means that it has actual power to shape policy.

It Survives Leadership Changes

The true test is when the power goes to a new set of hands. Does the losing party acknowledge the outcome? Is the new leader loyal to the constitution?

Rights Are Protected In Practice

Listing rights isn’t enough. People should be able to actually exercise them without fear.

The System Self-Corrects

If there is something wrong, the constitution should have affordances for what to do to fix it that don’t involve insurrection and revolt.

It Adjusts Without Shattering

The constitution need to adapt with times without the central tenets shaking.

Real Examples: What Is Working in the World

Various countries have pursued various solutions:

A Lesson From Germany

Germany has “eternity clauses” in its constitution that may never be altered — even if the Nazis were to return tomorrow — designed to preserve human dignity and democracy forever.

Switzerland’s Direct Democracy

Voters who submit their own proposals for constitutional amendments in Switzerland can also vote on them directly, leading to a high level of public engagement.

India’s Social Justice Focus

India’s constitution directly speaks to historical discrimination and mandates affirmative action to deal with oppression of certain groups.

Canada’s Charter Evolution

Canada appended its Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982, demonstrating the viability of existing constitutions to evolve.

New Zealand’s Flexibility

New Zealand has no single written constitution, but rather a body of laws and traditions that interact to constitute the national power structure, demonstrating there is more than one way.

Your Constitution’s Long-Term Health

Picture your constitution as the foundation of a building. You don’t take that foundation away on a whim, but you do need to care for it.

Create traditions around your constitution:

- An annual day of reflection on constitutional values

- Standard citizenship ceremonies, which stress the concepts in the Constitution

- Prizes honouring constitutional public servants

- Museum or exhibit about constitutional history

These traditions turn your constitution from a legal document into an organic part of culture.

Conclusion: The Constitution as a Living Promise

A constitution is essentially a promise — from one generation to the next, from government to citizen, from strong to weak. It is a commitment to governing on the basis of limited power, the rights of citizens and justice.

But promises are only as good as those who make and keep them. The best constitution in the world will fall, if citizens don’t care about it, leaders pay no attention to it or there’s little energy for enforcing it.

Crafting a constitution that works in practice takes wisdom, humility and courage. Wisdom to learn from history. Humility to know that you can’t plan for everything. Strength to stand up for rights even when it isn’t popular.

These principles hold whether you’re making rules for a nation or as the board of a neighborhood association. Start with clear values. Disperse power so no one has too much. Protect fundamental rights. Develop avenues for flexibility when necessary. And, finally, build a culture of people who care about following the rules you’ve established.

Your constitution is your guide to the future. And make sure that it leads somewhere worth traveling to.

Frequently Asked Questions

Most successful constitutions are between 5,000 and 20,000 words long. Anything shorter would be too vague, anything longer almost certainly has material that belongs in general laws instead. The U.S. Constitution is about 4,500 words versus India’s at around 145,000. This doesn’t make one right and the other wrong. But when it comes to being democratic, short generally makes sense for its citizens to comprehend and remember what governs them.

Technically yes, but it’s rare. The main reason to have a constitution is to limit power, and that’s always going to be most meaningful if there is some democratic accountability. Some monarchies are constitutional, where the power of the king is restricted. But under dictatorships, constitutions are formal documents that are not implemented.

A constitution is the supreme law of the land — but it does not float in thin air. These laws must conform to the constitution and can be amended or repealed in accordance with the conventions of government. You can think of the constitution as the rules for making rules.

This is debated. Constitutions in some countries declare capitalism or socialism, but that can be constraining. Better to enshrine economic rights (property, workers’ protections) — and leave the fiddling over specific economic policies to normal legislative action in a changing world.

A good constitution anticipates crises by providing for emergencies, clear succession in government and mediation of conflicts among branches. When the constitution is ambiguous, countries frequently have recourse to supreme courts to interpret it, or in extreme cases convene constitutional conventions.

That is why judicial review is so vital. An independent supreme court or constitutional court should have the last word on what the constitution means. Their interpretations create precedents for later acts.

Some constitutions have “unamendable” provisions that insulate core principles from being changed, like human dignity in Germany’s constitution. But in the end, the most reliable check is having a citizenry that cares enough about its constitution to defend it.

This depends on your society. Some secular constitutions make a clear distinction between church and state, whereas others include religious references in their preamble or constitution. The point is to defend religious freedom for all, and that no one creed should subdue others. The middle way for many countries is to protect religious practice and maintain a secular government.

There’s no fixed schedule. The U.S. Constitution has 27 amendments and yet it is over 230+ years old. Since 1789, there have been 15 different constitutions in France. And quality matters more than quantity — only make switches when you really need to, to solve an important issue or respond to changing conditions.

Though each section is important, the most crucial might be who holds power. In the absence of adequate checks and balances, the best-drafted rights can be flouted by those in power. The thing that stops power corrupting is what ultimately defends everything else.