When you think of countries, you most likely envision things like the United States, France or Japan. But there are so many small countries most people have never heard of. These are micronations, and they have their own governments, leaders and laws. Some are on small islands, others in people’s backyards and a few only online. What’s interesting about these mini-countries is how they are run. To help bring some of the world’s best-known micronations to life, here’s a look at the power structures behind them.

What Distinguishes a Micronation from an Actual Country?

But what are they, right? Before we get into how, exactly, micronations operate, let’s first look at what they actually are. A micronation is a land that says it’s an independent nation but isn’t acknowledged by real countries or the United Nations. It’s as if you decided to be your own country in your bedroom—you can make rules, design a flag and even print currency but the rest of the world won’t take you seriously.

There are three principal attributes that real countries have: a permanent population, a defined territory and recognition by other countries. The first two are all but ubiquitous in the world of micronations; you never, on the other hand, get the third. That doesn’t prevent their leaders from establishing forms of government, however. Some micronations are serious political aspirations; others are larks.

The people who manage micronations employ all manner of systems of government. Some have copy monarchies and kings and queens. Others, elections and voting democracy give it a go. Some of them have one leader who makes the final decisions. Who holds the power will be based on what the founder wants and who’s living there.

The Principality of Sealand: A Fortress for a Family

One of the most well-known micronations is located on a rusted platform in the North Sea, seven miles off the coast of England. Sealand began life as a military fort during World War II, but it was abandoned once the conflict had ended. In 1967, a man named Paddy Roy Bates seized the platform and proclaimed it an independent nation.

How Sealand’s Government Works

Sealand is a principality, because it’s governed by a prince. Roy Bates declared himself Prince Roy, who was succeeded, after his death, by his son Michael. This is a dynastic monarchy—power comes from the family. Prince Michael has the last say on everything in Sealand, from laws to who is allowed to visit.

Simple as far as governments go, Sealand being minuscule. There is the Prince at the top and then there are some dudes with fancy titles like “Prime Minister” or “Minister of Foreign Affairs.” Most of these jobs are retained by family or friends. No parliament, no voting system—who would there be to vote for anyway?

The Power Structure Breakdown

Position: Prince

Current Incumbent: Michael Bates

Responsibilities: Monarch, head of the executive

Position: Government Officials

Current Incumbent: Family Members

Responsibilities: Day-to-day administration

Authority: Based on laws and Sealand’s people

Subordinate Authorities: May be addressed if needed

Members: Limited

Titles: May offer them to others

This is what makes Sealand’s power structure interesting: it’s serious and playful at the same time. The Bateses are serious when they say Sealand is an independent state, but they also sell noble titles via the internet to make ends meet. For about $50 you can become a “Lord” or “Lady” of Sealand. Not that these acknowledgments come with any real power.

In the meantime, Sealand has really had to defend its authority. A German businessman staged a coup and claimed the platform while Prince Roy was absent for a time period in 1978. Roy had to arrange for a helicopter rescue, so his country could be saved. That demonstrates that even in a micronation, it is all about holding territory.

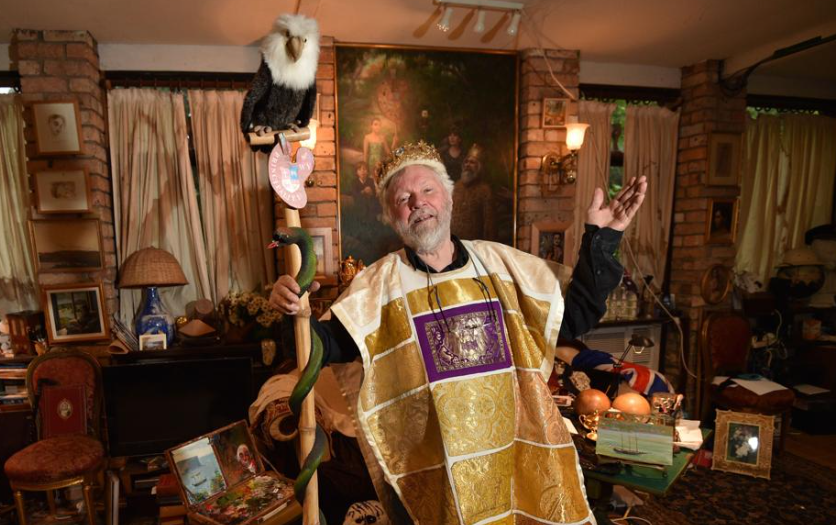

The Republic of Molossia: A Just-for-Fun Pretend President

A micronation the size of a city block in the Nevada desert. The Republic of Molossia is 1.3 acres and has existed since 1977. It is the creation of Kevin Baugh, who remains the president. Molossia, unlike the monarchy of Sealand, is a republic of democratic character.

The Presidential System

Molossia’s founder and president, Kevin Baugh. He’s re-elected every couple of years, but get this—he is usually the only candidate and among the few voters. Most of Molossia’s population consists of his family members. This leads to a paradoxical situation, in which democracy is established on paper only and real power rests with a single person.

President Baugh has organized an entire government with various departments. There is a Department of the Navy (even though Molossia is fully landlocked), a Space Program, and several other offices. The president is the sole participant in all of these or joined by his family. We just pretend we’re in government, but Baugh actually believes it.

Why This Structure Works

The power dynamic in Molossia operates because everyone participating is well-aware it’s almost entirely symbolic. President Baugh is making no effort to pretend he isn’t behind all this—Molossia is his baby. The “government” is really there just to prove a point about independence and self-determination, not because lots of people need ruling.

Molossia has its own currency, the Valora, its own time zone and, of course, its very own space program. The president runs all of that stuff. When it’s time to make a decision, there is no elaborate voting process or debate—President Baugh makes the call and that’s the end of it. That makes the government very efficient, at least in theory, if not terribly democratic in practice.

Freetown Christiania: The Power of the People

Presidents and princes are not standard-issue in the world of micronations. Copenhagen’s Freetown Christiania operates on an entirely different structure. Established in 1971 by a group of hippies and activists who invaded an abandoned military base, Christiania is home to about 1,000 residents and organized according to rules they draw up collectively.

The Power of the People

Christiania is without a ruler or president. Instead, decisions are made in large gatherings where everyone can attend. This is known as direct democracy or consensus decision making. When it comes to making important decisions, villagers meet and discuss until they come to a decision that everyone agrees with.

There are various working groups that deal with specific tasks such as garbage removal, building repairs and external relations. These groups are coordinated, but a coordinator isn’t the boss—think more of an organizer kind of making sure things get done. Anyone can sign up for a working group and help shape the way things are done.

Challenges of Collective Leadership

That sounds fair, but as with any kind of power structure, there are issues. If everybody wants to talk, meetings can last for eternity. In some cases, a strong personality takes over the conversation automatically when there’s no official leader. And when quick decisions need to be taken, the system can be too slow.

There is also heat from the Danish government, which has attempted to close it down several times. Lacking a single leader with whom to negotiate, Christiania becomes more difficult for outside authorities to approach. The Danish government does not know who is “in charge” because no one really is.

Nevertheless the spirit survives. Christiania still celebrates 50 years and is still standing. On the whole, the power structure would be designed to produce a community of strong solidarity since everyone has a right in decisions. People are more committed to making things work when they feel heard.

Hutt River: Where Business Becomes Royalty

It resulted from a dispute with the Government by wheat farmer Leonard Casley in 1970. His solution? Announce independence and start his own country. The Principality of Hutt River endured until 2020 and was an example of how micronations can also incorporate business interests into royal power structures.

The Royal Business Model

Prince Leonard (that’s what he called himself) operated Hutt River as if it were a business in the guise of a kingdom. He was the king, after all—and that meant that in his 75-square-kilometer kingdom, he was the one in charge. But Prince Leonard didn’t aspire to classical riches, he had a practical end in mind: the prince wanted to farm without government restrictions and earn money from tourism.

The hierarchy was clear: Prince Leonard at the top, his family in subservient roles, and that was all. There were fancy titles that came with no power, like “Minister of State” and “Secretary of State,” but these were for family members and mates. All actual power resided with the prince.

Tourism as a Power Tool

But what really set Hutt River apart was the way it leveraged its governmental infrastructure to lure unsuspecting tourists. Visitors loved coming to a “country within a country” and meeting an actual “prince.” Visitors could have their passports stamped, purchase Hutt River currency and pose for photos with the royal family. The power structure wasn’t about control alone—it was a tourist destination.

Prince Leonard struck his own stamps and coins, even honours and medals. They brought in money and made the pretense of a normal government. By behaving like a real country, Hutt River felt more “real” to people—even though no other country recognized it.

The principality dissolved in 2020 following the death of Prince Leonard and the decision by his heir not to maintain it. That demonstrates that small family-run micronations are generally purely ego-driven and owe themselves entirely to the strength of will shown by their creator. When the leader’s interest falls, or when the leader dies, the entire nation can come apart.

Liberland: Cyber Democracy and the Blockchain State

Among the most recent and peculiar micronations is Liberland, which was established in 2015 on a pocket of no-man’s-land between Croatia and Serbia. Liberland is different because its power structure is explicitly meant to marshal today’s technology—things like the blockchain and cryptocurrency—to create a new kind of government.

The Vision of Distributed Power

Liberland has a president, Vít Jedlička, who is his country’s founder, but he doesn’t want to be a conventional ruler. He wants to build a government of power through technology. Neighbors could vote on laws using blockchain, and smart contracts would automatically enforce rules rather than through the police or courts.

At the moment, Liberland’s government primarily operates online because Croatia won’t let people live on its land just yet. There is a president, ministers and representatives in the government, only they are distances away. Thousands have applied for citizenship, but few have actually walked on the land.

How Blockchain Changes Government

In conventional governments, you need people to operate stuff—judges to hear cases, police officers to enforce laws, bureaucrats to handle paperwork. Liberland aims to automate many of these functions with computer code. Instead of having a judge resolve a dispute, for instance, they use smart contracts to automatically implement whatever agreement people reached.

This is a very different power structure. Instead of power moving from top to bottom (as in a monarchy), or from bottom to top (as in a democracy), it would be encoded in computer programs that no single person controls. It’s an experiment in whether you can have government without traditional leaders.

The issue is, that Liberland can’t properly test this out, as it’s not allowed to utilize its territory. The power structure remains theoretical. President Jedlička has power today, though if Liberland becomes a fully functional nation, his position will need to diminish and blockchain systems will take over.

The Aerican Empire: Leadership Via the Internet and Absurdist Politics

Some micronations are virtual, and exist only on the internet. The Aerican Empire was formed in 1987 and claims land on Earth, as well as territories on the planet Mars and one or two other planetary bodies. It’s ruled by an emperor but functions largely through online communities. This illustrates how structures of power can exist without actual territory.

The Emperor’s Domain

The Aerican Empire has an emperor (Eric Lis) who is the final decision maker, but day-to-day operations take place through email listservs and social media. Citizens are scattered around the globe, participating in the “empire” via the internet. There are provinces on Earth and colonies on fictional planets, all of which has its own governor.

The power dynamic is ostentatiously absurd. There is an emperor, but he isn’t a dictator. There are laws, but they’re frequently jokes. The job of government is to amuse and bond people, not exert actual control. This is a power structure of voluntary association—and if people stop wanting to participate, it all comes apart.

Why People Accept an Imaginary Emperor

The Aerican Empire invokes the question: where does power get its force? In real countries, power emanates from the capacity to enforce laws with police and armies. It is consent that makes the Aerican Empire powerful. The emperor has power because citizens consent to believe that he does.

Such a micronation demonstrates that power structures do not always require territory or force of arms. They can be present by way of shared imagination and community consent. The emperor’s power is real within the game, even if it has no weight elsewhere.

Typical Micronation Power Structures

When you study various micronations, certain patterns emerge. Each micronation generally has only one founder with a vision. Whatever name they choose, the person who becomes that generally gets to be in charge. The founder’s essence defines the entire power structure.

Founder-Centered Government

Nearly every successful micronation is wrapped around one charismatic individual. If you are referring to a creative project, it is this individual who brings the type of enthusiasm and dedication required to sustain momentum for the project. And when that person dies or loses interest, so does the micronation. This is also fundamentally unlike actual countries, which have legal mechanisms to facilitate the peaceful transfer of power.

Micronation governments have strong family elements. Since there are never very many citizens, founders hand over key posts to relatives. This results in dynastic structures even in the smallest of micronations that supposedly are democratic. You’d rather entrust the imaginary country to family than strangers.

The Importance of Symbolism

Micronations spend a great deal of time on symbols of power—flags, currencies, stamps, titles, and official looking papers. These icons help to foster a sense of an actual government. A microstate with a professionally-designed flag and currency appears more “legitimate” than one without them.

Power in micronations is generally more representative than effective. A president of a micronation can’t actually compel anyone to do anything. But the symbols and structure forge a psychological reality in which people take on roles with seriousness, are made to feel part of something official. This is among our prompts for looking at this ruled world we inhabit.

Why These Power Structures Matter

You may ask yourself why anyone is interested in how fake countries are governed. But there are actually important truths about real governments that micronations can teach us. They are a reminder that power arrangements are held together in part by belief and agreement. It’s easy to look at actual countries as something permanent and natural, when they too are constructed on the basis of people agreeing to submit to certain rules and authorities.

Micronations also play with alternative forms of organizing society. The group decision-making of Christiania, the blockchain democracy of Liberland and the benevolent dictatorship of Molossia all challenge traditional governance. A few of these experiments may even affect actual political thought. For more information on how nations form and gain recognition, visit the United Nations member states page.

The Psychology of Authority

Micronations offer a lesson in authority and how little there needs to be. Put somebody in a uniform, give them a title, forge some official-looking documents and people will start treating him like he has some real authority. This happens even though everyone knows it technically isn’t real.

And this is important because it tells us something essential about human psychology: we’re wired to see and respond to symbols of authority. To this end, would-be micronation leaders use the potent symbols of nationhood to form real communities, in the absence of armies and police forces.

The Future of Micronation Governments

With technology advancing, micronation power dynamics could also develop in complexity. With blockchain, virtual reality and digital currencies, micronations might be able to build much more elaborate governments without any physical space. Think of a micronation that resides entirely in virtual reality, with citizens tuning in to participate from each corner of the world through VR headsets.

Some believe that micronations might become more significant as people grow disillusioned with traditional governments. If a place like Liberland can successfully show that blockchain governance works, it could change the way real countries think about democracy and institutions.

Challenges Ahead

Legitimacy, still, is the chief hurdle for these would-be states. They cannot engage in international trade, travel abroad or negotiate deals with other countries in any meaningful way without the recognition of other nations. Their power structures are autonomous, and if real borders exist at all they shouldn’t matter for their being.

Another challenge is sustainability. The founder’s energy and vision sustain most micronations. Power structures that endure a founder are hard to build. Real countries get around this with constitutions and institutions, but micronations find it hard to develop such things well.

Lessons From Tiny Nations

What lessons can people get from examining the way that micronations are run? First, that hierarchies of power are flexible and resourceful. There’s no one “true” way to organize a society. Second, that legitimacy derived in part from belief and participation, not only from force. Third, that small communities must organize themselves in some sort of structure to get things done.

Micronations also show us that tinkering with systems of governance can be fun and educational. So the leaders of many micronations are effectively executing a hands-on civics project. They’re learning how laws work and how to resolve disputes, and they’re discovering how to build communities by actually trying to do it, no matter how small the scale.

The power structures governing prominent micronations go as far back to a medieval monarchy to a futuristic blockchain democracy. Some are earnest political statements, others elaborate jokes, and many fall somewhere in between. What all have in common, however, is a sense of faith that ordinary individuals can make their own governments, enforce their own laws and form their own communities—even if the broader world refuses to take them seriously.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can micronations exert real legal power on their citizens?

No, micronations are not legally enforced by any legitimate government. If you reside in a micronation, however, the laws of the real-life country in which that land is located still apply to you. Laws of a micronation are only enforceable if they are agreed to be followed by people voluntarily.

How do micronational leaders enforce their laws?

Few micronation founders can enforce rules the way actual governments do. They depend on voluntary compliance and social pressure. If individuals violate the rules of a micronation, they generally face the worst punishment of exile or being ostracized by other citizens. Micronations don’t have real police forces or jails.

Has a micronation ever been recognized?

The United Nations and established nations have not recognized any micronation. Some, like that of Sealand, have made for interesting legal cases but none have won true independence. Recognition involves other countries agreeing that you are a country, which is very hard to do.

Who is the most powerful person in a typical micronation?

In general, the founder holds all the cards. Whether they adopt the honorific title of president, prince or even emperor, the person that founded the micronation generally gets to make the most crucial decisions. Relatives of the founder frequently are holding informal power positions.

Why do people make up micronations if they aren’t real countries?

People found micronations for a wide range of reasons: existential statements, as acts of political protest, artistic projects, just for fun and amusement but also to experiment with forms of government or generate a certain type of community. And the motivations can be as varied as the micronations themselves.

Can you get citizenship in a micronation?

Many micronations will accept you as a “citizen,” and you can often apply online. Some are free, others charge fees. But it’s not like this citizenship comes with any legal rights in an actual country. For the most part, it’s symbolic—but also can put you in touch with a great network of people who have similar interests.

Do micronations have taxes and economies?

Most micronations generate their own money and have a tax system, but these things are only functional when confined to the realm of a few thousand other micronationers. Citizens of micronations are still required to pay real taxes to the actual countries they live in. Some micronations earn money through tourism, selling titles and selling collectible items such as stamps and coins.

What becomes of a micronation after the leader passes away?

This varies by micronation. In a monarchy such as Sealand, leadership is handed down to the ruler’s children. A few micronations have disbanded after a founder died, or lost their interest. Hardly any micronations have managed to establish stable systems of power transfer that are functional beyond the lifetime of one or, at most, two generations.