Ever wanted to start your own country? It might sound like material from a fantasy novel — but thousands of people around the globe have indeed done it. That’s the term for these small, self-declared nation states known as “micronations” — and they can vary from serious political projects to whimsical social experiments.

Micronations are human and so are bound to be like real countries in important ways. They have no official recognition from the United Nations or other governments, and most do not control real territory in the traditional sense. But that hasn’t prevented imaginative people from constructing intriguing communities with their own flags, currencies, governments and citizens.

Whether you’re intrigued about founding your own micronation or just looking to learn more about these unusual endeavors, there’s much to be learnt from the successful ones. Some micronations are rooted in political philosophy, while others aim to serve or ratify the environment, and some are purely playful or exist only for purposes of creativity. And all of them provide a slightly different perspective on what might make a micronation work.

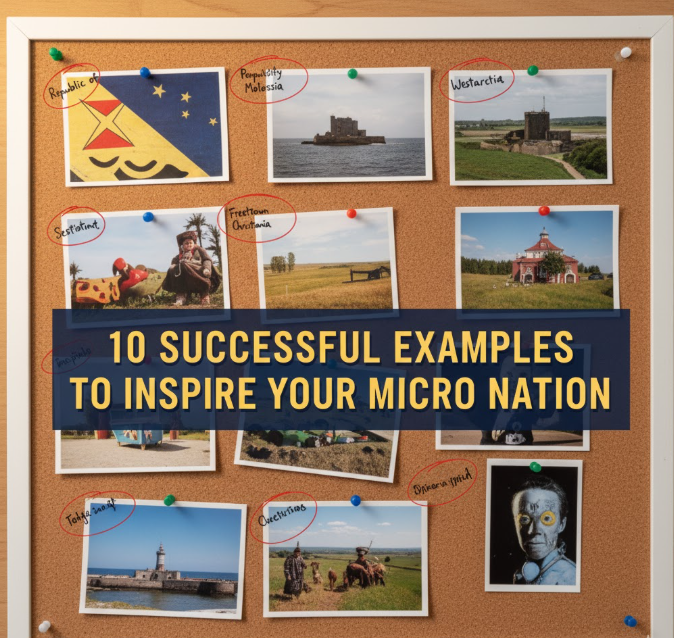

Here’s a list of ten of the most successful micronations. You will find out what made them so special, how they attracted citizens and what lessons they hold for anyone who has ever thought about founding their own tiny country. From an ocean platform to a farming commune, these are some of the absolutely wild variety of micronational projects that exist.

What Makes a Micronation Successful?

But before we get into the weeds, so to speak, of tangible examples, what exactly does “success” look like for a micronation? Micronations can’t be judged by traditional measures like GDP or military power, unlike “normal” countries. Instead, success takes many shapes.

A successful micronation mostly has clearly-defined goals it actually works toward. Others want to try out different styles of government. Others seek to preserve the environment or build artistic communities. The top micronations are clear in what they try to accomplish and stick to that vision.

Longevity matters too. Many micronations are declared with a lot of pomp and ceremony but last only a few months. The ones that truly succeed endure for years or even decades building real communities and creating lasting impact. They develop systems which still work when founding members have died or moved on.

Community involvement is another critical aspect. The most effective micronations are able to recruit committed citizens who actually take part. They build cultures, traditions and shared experiences that make people want to keep participating. Without active citizens, a micronation is just a webpage or a scrap of paper.

Finally, the model micronation succeeds when it can offer something unique. They provide reasons for people to pay attention, to get involved — whether it’s the novelty of a new political system, the beauty of a place or an intriguing narrative.

Sealand: The Maverick State That Didn’t Sink

In the middle of the sea, seven miles from shore off England’s northern coast, rises a World War II defense against Nazi Germany that also gave rise to Britain’s most famous micronation: the Principality of Sealand, among Earth’s most famous micronations. Founded in 1967 by Paddy Roy Bates, a former major in the British Army, Sealand has lived for more than 50 years—longer than many other micronational efforts.

Bates seized the disused fortress named Roughs Tower because Britain’s territorial waters did not reach that distance at the time. He declared independence, named himself Prince Roy and set about creating a tale that would become legendary. It has a flag — red, white, and black; a constitution; national anthem; currency (the dollar of Sealand); even passports.

What’s truly extraordinary about Sealand is how it has defended its independence. In 1968, British warships drew near, and Bates shot off a few warning rounds to drive them off. Britain tried to take him to court, but judges said they had no jurisdiction because the platform was outside territorial waters. It enabled Sealand to maintain a legal argument that exists to this day.

Sealand weathered its greatest crisis in 1978 when a consortium of German and Dutch businessmen occupied the platform while Roy was away. They kidnapped his son Michael and seized power. Roy led a helicopter counterattack with armed friends, retook the platform and held the invaders as prisoners of war. It even prompted Germany to send a diplomat to negotiate their release, an act which Sealand regards as unofficial recognition.

The tiny nation has been using innovative tactics to reel in cash. It hawked noble titles and citizenship documents over the internet, signing up thousands of “citizens” around the world. It franchised its name to be used in a variety of products and services. At one time, it was even considering hosting internet data servers in the building to capitalize on its dubious legal status.

Key Lessons from Sealand:

- Concrete terrain, including unusual areas, lends credibility

- Arguing sincerely for your position is what makes people respect you

- Growth and revenue strategies that are not subscription-focused keep the lights on

- A good story makes headlines and fans

- Family line of succession guarantees continued survival (Michael now operates Sealand)

Freetown Christiania: The Hippie Haven in the Heart of Denmark

In 1971, a collection of hippies and activists infiltrated an abandoned military barracks in Copenhagen, Denmark and established it as a free commune. And so Freetown Christiania was born, and within a few years proved to be one of the world’s most successful intentional communities.

Christiania operates semi-autonomously within Copenhagen. Although not entirely separate from Denmark, it operates under its own laws and system of government. The residents govern themselves, making decisions by consensus at community meetings. For half a century or so, the direct democracy model has kept about 1,000 residents engaged.

The compound was built on three founding principles: no hard drugs, no private cars, and no weapons. These commonsense rules established a framework to balance freedom with safety. Christiania has its own flag, street signs and even its own brand of architecture, with imaginative buildings painted every shade but Danish-government-approved beige.

What made Christiania unique was how it combined art, alternative lifestyles and commerce. The well-known Pusher Street became known for cannabis sales, which the Danish authorities turned a blind eye to for decades. Although controversial, this gave rise to the economic life of the community. Outside the drug market Christiania is also home to a concert venue, art galleries, restaurants and workshops that draw hundreds of thousands of visitors each year.

The community has withstood several attempts by Danish governments to close it or normalize it. In 2012, they negotiated a group purchase of the land and thus their future. That was a lot of organization for a community that supposedly operated on anarchist principles.

Christiania is proof that alternative forms of governance can work at a significant scale. Its economy makes millions of dollars, its buildings are kept up and it houses those who may not function as well in mainstream society. Similar projects have also been inspired by the community around the world.

Key Lessons from Christiania:

- Clear, simple policies make communities work

- Striking a balance of freedom with responsibility draws long-time residents

- Economic sustainability requires creative approaches

- Value of learning to tolerate the structures surrounding authorities

- Community commitment is stronger than imperial control from above

Hutt River Province: The Farming Uprising That Became a Tourist Attraction

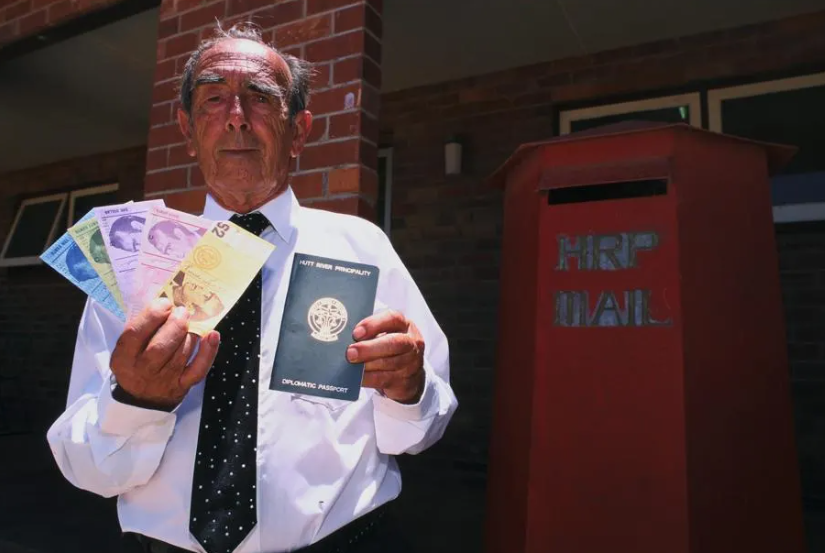

Leonard Casley had simply wanted to save his wheat farm. When the Australian government placed stringent wheat quotas in 1970, Casley exploited a little-known legal loophole to secede from Australia by declaring an independent sovereign state on his 75-square-kilometre (29 square miles) farm in Western Australia called the Hutt River Province Principality.

What began as a pragmatic answer to agricultural policy grew into a 50-year micronational experiment with global appeal. Casley named himself Prince Leonard, and he ran his principality until his death in 2019. At its height, Hutt River proclaimed a population of more than 13,000 citizens around the world – but hardly any lived on the physical property.

In many ways, Hutt River seemed like a real country. Its own money, postal service and stamps as well as its own time zone (15 minutes ahead of Western Australia). Prince Leonard also issued passports, some of which his subjects are said to have used for overseas travel, despite their dubious legality.

The principality’s principal achievement was economic. It turned into a popular attraction, with tens of thousands of visitors each year who paid admissions and purchased souvenirs. The gift shop peddled passports, citizenship certificates, stamps, coins and title appointments. This tourist income kept the Casley family afloat for many years.

Prince Leonard was extraordinarily adept with the media. He made international visits, met with government officials and sought to portray himself as a serious head of state. With his formal uniforms, ceremonies and diplomatic-sounding language, Hutt River seemed more legitimate than many other micronations.

The “sovereign principality” was not even immune from Australian attempts to regulate and tax it. The Australian Taxation Office would later declare for Casley to eventually pay millions of dollars in back taxes, penalties, and interest. Following Prince Leonard’s death, his family couldn’t keep it going, and Hutt River most recently came to an official end in 2020.

Even after its demise, Hutt River demonstrated the extent to which a micronation could support itself economically over decades and build an actual tourist industry.

Key Lessons from Hutt River:

- Sustainable income from tourism works for micronations

- Physical space creates opportunities for visitors to explore

- Personality and leadership can carry a project through

- Government connections are key (even if they’re not so friendly)

- Long-term sustainability requires succession planning

Liberland: The Digital Country Insurgent on the Danube

Established in 2015 by Czech politician Vít Jedlička, Liberland is a modern expression of micronationhood. It lays claim to a contested area of some 7 square kilometers between Croatia and Serbia along the Danube River that neither country effectively controls.

Liberland is founded on libertarian ideals, with little government control, low taxes and maximum freedom for its citizens. It has adopted “Live and Let Live” as its slogan, and in the constitution it drafted, those principles include individual freedom, free market economics and restricted state power. Through this ideological clarity, true support from various powers around the world has been brought up.

One of the reasons that Liberland is so successful is its willingness to utilize advanced technology. It has elicited more than 700,000 citizenship applications, although most of the applicants do not expect to live there and would prefer if others did not live nearby either. The country has created blockchain-enabled platforms for governance, land registry and its own currency, Merit.

Liberland has also achieved some recognition. Representatives have travelled to international conferences, and cordial relationships have been established with one or two politicians in different countries, at an informal level. It has “representative offices” in various cities around the world, acting much like embassies.

The project was immediately challenged with Croatian police blocking access to the territory. Nevertheless, Liberland has soldiered on with its meetings and events in neighboring cities, as well as the development of its virtual works. The residents organized a physical attempt to settle in 2015, but Croatian authorities prevented them from reaching the site.

But Liberland is a case study in how a micronation can thrive as largely a digital and ideological endeavor. Few citizens travel to the declared territory, but they engage in online governance experiments, economic activities and community formation. The project accumulated a huge sum of money by crowdsales in cryptocurrency, showing call-and-find true fundraising tendencies.

The nation has held conferences on boats floating in international waters, developed educational programs around libertarian governance and cultivated supporters from around the world. This demonstrates that a piece of physical land, while useful, isn’t strictly necessary for a micronation to be effective.

Key Lessons from Liberland:

- Clear ideology attracts committed supporters

- Digital tools enable global participation

- Blockchain and cryptocurrency opens up a host of possibilities

- Other models of territoriality are possible

- Reputation and media relations are just as important

Seborga: The Old Principality That Woke Up

In 1963 Giorgio Carbone, president of a flower co-operative in the Italian village of Seborga, stumbled upon an unprecedented find in some historical files. He came across documents that showed Seborga having been an independent principality in medieval times, and that it had never been formally integrated into Italy by the proper legal process.

Carbone persuaded the inhabitants of his village to vote him in as Prince Giorgio I, and Seborga was reborn. Unlike most other micronations, Seborga had something special: a whole town in an attractive location that could operate as a real tourist attraction. The village, home to about 320 people, is nestled in the Italian Riviera near Monaco amid beautiful vistas.

Seborga proceeded with little interference from Italian authorities. Residents paid Italian taxes, and followed Italian law, but they also assumed a principality persona. They even produced their own money (the Luigino), coined coins, issued stamps, and appointed a small guard in ceremonial costume.

Prince Giorgio was an astute promoter. He was featured in untold media stories, adorned himself in princely finery and regaled visitors with charm and wit. He was playful but also serious enough to keep people interested. He was the prince for 46 years before he passed away, leaving behind an astounding collection of memories and real community involvement.

The principality became an economic factor in the village from tourism. Tourists flocked to the area to visit the “country within a country,” spend money on Seborgan coins and stamps and bask in the offbeat atmosphere. Neighborhood business owners were grateful for the extra foot traffic and press.

Following Giorgio’s death, the inhabitants elected Marcello Menegatto as new prince. This was a peaceful succession, indicative of institutional solidity. The new prince has largely continued his country’s approach, keeping Seborga moving forward without going too far over the line with Italian authorities who mostly treat it as local color.

Seborga shows it’s possible to get legitimacy from historical claims, even if they’re on the dodgy side. It also demonstrates the significance of community buy-in, as well as how micronational identity can enhance local pride and economic opportunity.

Key Lessons from Seborga:

- Historical narratives provide compelling foundations

- Community involvement creates authentic micronations

- Unique and quaint is the lifeblood of tourism

- Intelligent coexistence with host nations is useful

- Smooth succession maintains continuity

Molossia: The Little Backyard Nation That Could

The Republic of Molossia was founded by Kevin Baugh in 1977 as a project with his friend during their childhood. Now, decades later, he still runs it — all from his home in Nevada — and it is one of the most professionally presented micronations on the planet.

Today, Molossia comprises roughly 11 acres of Baugh’s property — land which he proclaimed independent in 1999. The nation has all the trappings you’d expect of a country: government, military (Baugh himself), space program (model rockets), postal service, customs office, bank and national railroad (a garden railway). Baugh is the President, and he even acts like it.

The difference is in the details – and Molossia has many details and professionalism. Baugh developed a full government system complete with laws, rules and procedures of official conduct. To enter, visitors must pass through customs (i.e. literally a customs booth) in which Baugh stamps their passports with the official Molossian visa stamp. The investment makes it feel realer.

Molossia has its own system of measurement and calendar. It follows “Norton time” (for Emperor Norton, a well-known San Francisco eccentric), 39 minutes ahead of Pacific Standard Time. It takes temperature in Fahrenheit, but refers to it as degrees “Molossian.” These idiosyncrasies make for a unique national character.

The country jokingly declares itself to be at war with East Germany (which no longer exists), and insists it is still at war. This quirky style has helped Molossia garner attention in the media without being laughed out of the room. Baugh strikes an effective mix of earnest delivery and enough self-consciousness to keep it real.

Molossia receives visitors by appointment, and thousands have passed through over the years. And Baugh gives tours of the nation, pointing out national landmarks and giving lessons on Molossian history in exchange for souvenir sales. This has helped with coverage of the country, with major international media outlets covering it resulting in attention on a scale which most micronations fail to achieve.

The country also conducts foreign relations with various other micronations, concluding treaties and such to that effect. This collection of micronations work together for support and legitimacy.

Key Lessons from Molossia:

- Trust isn’t instilled by flashy gimmicks; instead it’s earned via consistency and long-term commitment

- Professional presentation elevates perception

- The blend of earnestness and playfulness works well

- Founders contributing personally lead to success

- Complete systems make it feel more real

Ladonia: The Driftwood Country of Brother Cream

Swedish artist Lars Vilks erected two large driftwood sculptures, Nimis and Arx, on a rocky beach in southern Sweden in 1996. When local officials ordered them taken down, Vilks pulled a stunt: He proclaimed the place sovereign territory and dubbed it Ladonia.

Ladonia is in large part a conceptual art project and an internet community. The physical territory consists of some 2.5 acres of rocky coastline. The nation, however, claims over 20,000 citizens from all around the world — most have never set foot here. The citizens unite online and receive citizen certificates and membership of the virtual community.

The nation’s government is designed to be preposterous. It has a queen, Ywonne (a sculpture in actuality), and other ministers, along with an intricate bureaucracy that satirizes modern government. The official language is Latin, but no one actually speaks it. This artful approach has everything to do with why Ladonia is about ideas and not so much about reality.

The secret of Ladonia is its commitment to absurdity and creativity. The sculptures themselves became famous in the world of art, and the notion of a micronation simply made their impact even more far-reaching. Vilks devised a full-blown mythology of Ladonia, with national holidays, customs and cultural norms.

Eventually, Swedish authorities came to a compromise with Vilks. The sculptures still stand and receive thousands of tourists every year. The spot has grown into a de facto tourist destination, with signs reading “Ladonia” pointing visitors the way. It’s a demonstration of how micronations can go from controversial to accepted.

Ladonia also became an emblem of artistic liberation and opposition to red tape. And when Vilks began receiving threats from extremists for provocative pieces in the later decades of his career, Ladonia fans came to his defense. The micronation community provided a true support network.

The country sells hereditary titles of nobility at a profit, receiving some money and spending more time as part of volunteers. People produce Ladonian art, write about Ladonian philosophy, and meet in assemblies. In other words, the community is formed through common engagement with the creative idea.

Key Lessons from Ladonia:

- Art and imagination can form a basis for micronations

- People are drawn to comedy and absurdity

- Virtual citizenship works when combined with physical landmarks

- Symbolic resistance resonates with people

- Physical art creates lasting landmarks

Forvik: The Island That Declared Itself Independent

A man named Stuart Hill led his boat to the minuscule Shetland Island of Forewick Holm in 2008, planted a flag on the island and claimed it for an independent Crown Dependency that he called Forvik. His justification was legalistic: he claimed that Shetland had not been properly transferred to Scotland and that it continued as part of direct Norwegian possession, thus his declaration was legitimate.

Forvik is one of those serious legal argument micronations, rather than fantasy ones. Hill, himself a former environmental consultant with no experience in harebrained projects, honestly thought that he was legally in the right and for years devoted himself to trying his case before various authorities.

The country granted citizenship and plots of land to all who would come. Hundreds of people from around the world became Forvik citizens, sending modest fees in return for citizenship documents. Hill made a constitution based on old Norse law (Udal law), a visible legacy of which is still in some ways in force, under legal technicalities.

What was interesting about Forvik, however, is that Hill was willing to put his claims to the test. He also refused to pay council tax, claiming that Forvik had no allegiance to the UK. He acted as his own counsel in court cases, arguing the point of law on Shetland’s status. Once the police stopped pursuing him, they effectively shut out his allegations instead of investigating them.

Hill lived on the island in miserable conditions, evidence of some serious dedication. He built structures, settled in and survived both the weather and the loneliness. This physical investment helped lend Forvik legitimacy that desktop micronations did not possess.

Forvik also threw up some big questions about sovereignty and record claims. Although Hill’s claims were rejected by the UK courts, some legal analysts considered them intriguing. The project underscored how sovereignty is occasionally the product of historical happenstances and dubious legitimacy.

Hill himself eventually proved too old and infirm to remain on the island but Forvik lives on as an idea. The project demonstrated how the efforts of a few determined individuals armed with legal creativity can make serious micronational projects, even if (or especially because) you don’t succeed at your ultimate goals.

Key Lessons from Forvik:

- Legal arguments provide alternative foundations

- Personal sacrifice demonstrates commitment

- Testing claims through official channels provides legitimacy

- Historical research can reveal some intriguing situations

- Individual dedication can sustain projects

10 Successful Examples to Inspire Your Micro Nation

Lovely: The Micronation That Popped Up in a Passport

The Kingdom of Lovely was established in 2002 by British comedian Danny Wallace and is a part of a BBC television series, “How to Start Your Own Country”, originally broadcast in January 2005. A humorous experiment has today become a fairly vibrant micropower with more than 60,000 people.

Wallace declared independence of his London apartment and set out to found a nation. The television show chronicled everything: creating a flag (there was viewer input), writing a national anthem, creating laws, installing government ministers and making diplomatic overtures to real countries. The BBC documented the entire project, bringing micronations to mainstream audiences.

The Kingdom of Lovely worked, because it was made for accessibility and participation. Citizens could sign up online, vote on national decisions and visibly participate in shaping the nation. It was a more democratic approach, that did not simply solicit passive judgment.

Wallace attempted to have Lovely be acknowledged by reaching out to the United Nations, embassies and government officials. No one came forward to officially recognize Lovely but the comical efforts made for great television and taught viewers lessons about how international recognition really works.

Among the project’s creative stunts were establishing a national space program (a helium balloon with a camera), seeking to join the European Union and trying to establish diplomatic relations with other micronations. These events showed what countries do while also being fun.

Lovely raised issues about citizenship and national identity. Thousands of people became citizens, attended the national day celebration in London and felt part of something. And this demonstrated how a sense of nationhood could come about through shared experience and story.

The Kingdom ended when that TV show did, but its influence continues on. Most citizens of Lovely later made their own or joined other related micronations. Wallace’s handling of the publicity demonstrated how media and access could transport micronational ideas to a very public stage.

Key Lessons from Lovely:

- Media exposure accelerates growth

- Participatory approaches build commitment

- Entertainment value attracts attention

- Documentation teaches others

- Even short-term efforts can have long-lasting effects

Wirtland: The Nation Without Territory

Wirtland, which was formed in 2008, would take things a step further: It would be an actual nation, with valuable passport and all optics included — except it wouldn’t have any claimed physical territory. Launched by internet entrepreneur Pavel Medvedev, Wirtland is 100 percent a cyber-nation so it’s ideal for the age of digital.

The premise of Wirtland is that in the age of technology, there is no need to have physical territory. Men and women meet online, vote digitally to govern and organize communities over the web. The country is busy with digital culture, cryptocurrency and online services.

At its height, Wirtland had over 5,000 citizens from all corners of the planet. The country had a working arrangement of government with elected deputies, appointed ministers and regular serving legislative institutions. Voters introduced laws, discussed the policies and voted on the country’s direction online.

Wirtland issued digital citizenship certificates, as well as electronic identity cards. No formal status in traditional societies but actual participation in society. The country also invented its own cryptocurrency prior to the popularity of Bitcoin, demonstrating unique thinking on digital economics.

The country had alliances with other micronations and was a part of inter-micronational organizations. It forged connections with a few blockchain projects, as well as some digital identity endeavors. It was these associations that produced a network effect which made Wirtland more powerful.

Wirtland proved that states could exist whose primary form is ideological and digital. People who never met